Tengrinews.kz – Kazakhstan has handed down its first life sentence for the murder of a woman, in a landmark case that has sparked a national conversation about gender-based violence and justice.

The court in Atyrau sentenced two men to life in prison over the killing of 23-year-old Yana Legkodimova, a case that her mother, Galina, describes simply: “I came to court having initially lost.”

The Atyrau court found 24-year-old Rizuan Khairzhanov and 25-year-old Altynbek Katimov guilty of especially grave crimes. They were convicted under:

- points 7 and 8 of part 2 of Article 99 (“Murder committed by a group of persons, by prior conspiracy and for hire”),

- point 6 of part 2 of Article 202 (“Intentional destruction of another’s property by a group of persons by prior conspiracy”).

Both men were sentenced to life imprisonment in a high-security facility.

The court ruled that in autumn 2024 the men killed Yana, who had been in a relationship with Khairzhanov and was in love with him.

During the sentencing, presiding judge Zarema Khamidullina departed from the usual restrained tone of such hearings and addressed the defendants directly.

“You killed Yana because she loved you,” she said, adding that Khairzhanov’s attempts to discredit the victim only underscored his lack of remorse.

Throughout the trial, Khairzhanov claimed that Yana allegedly drank, used drugs and was connected with escort services. He also tried to portray her mother, Galina, as a threatening figure with “connections”.

In court, Galina looked at him and asked: “You were so afraid of me that you killed my daughter?”

Judge Khamidullina stated that the court did not accept the defendant’s attempts to shift blame onto the victim.

“By smearing the victim, you show that you still do not understand your actions and have not embarked on the path of correction. For several days you discussed the method of killing — cruelly, cynically, with laughter. You were not concerned about the victim’s condition, only about how to avoid arrest. Throughout the trial the court agreed with you on only one point: there is no justification for your actions,” she said.

“Daughter, I did everything I could”

The verdict was read in a packed courtroom. At the beginning of the proceedings, Galina often sat there almost alone. As the details of the case became known, more and more people started coming — ordinary residents, activists, journalists. The announcement of the life sentence was met with applause and shouts of approval.

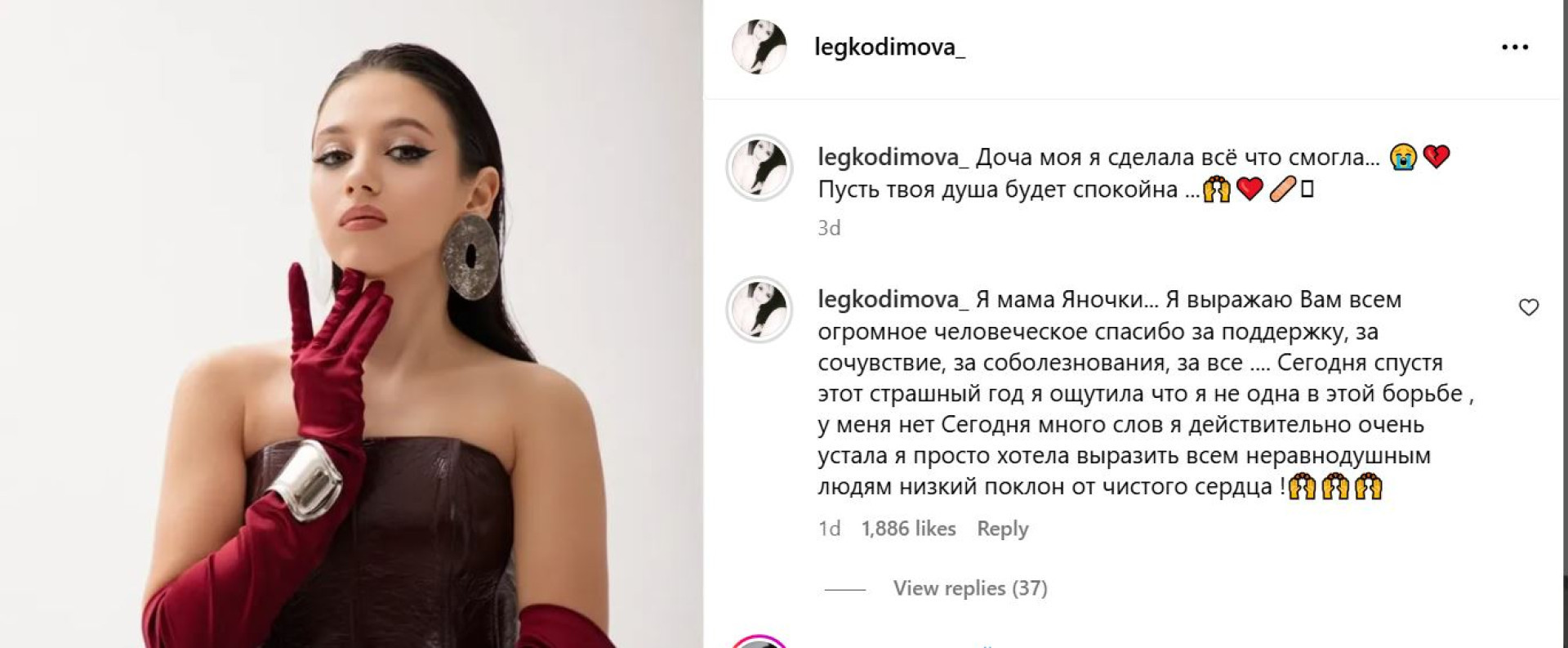

After the hearing, on the Instagram page where she once shared her daughter’s achievements, Galina wrote: “Daughter, I did everything I could. May your soul be at peace.”

Speaking briefly to Tengrinews.kz the next day, she said she still struggles to use the past tense when talking about Yana and declined a full interview.

“The only thing that helped me get through this was my boundless love for my child. The path was very long and very hard. I had no time to grieve — I had to pull myself together and go through every possible institution to find the truth,” she said.

From the first days, Galina was supported by the “Ne molchi” (“Do not be silent”) foundation, which helped bring national attention to the case and raised funds to pay for legal assistance. When she could not afford to fly her lawyer, Ajar Abdil, to Atyrau, social media users quickly collected the necessary amount.

Local residents also began attending the hearings simply to stand beside the mother.

“I couldn’t look away. I also have a daughter, and you inevitably imagine yourself in her place,” said Atyrau resident Olga T., who followed the trial as a public observer.

“You didn’t lose a breadwinner, just a child”

The fathers of both defendants took part in the court sessions as public defenders. They refused to speak to the media, but their statements in court drew wide public reaction once they were quoted by journalists.

Rizuan’s father, Aslan Khairzhanov, asked the court for leniency, describing his son as “kind and caring”, showing his certificates and publications and insisting that there were “too many assumptions and too few facts” in the case. He claimed there was no direct proof linking his son to Yana’s death and called the private messages between the two defendants “a joke between young men”.

His most controversial remark was made when the court discussed Galina’s civil claim for compensation — 25 million tenge in moral damages and 10 million tenge in material damages from each defendant.

“You didn’t lose a breadwinner, but just a child,” he told Yana’s mother.

This phrase caused outrage first in the courtroom and later online, where thousands of people had been following the case.

The second defendant’s father, Asylbek Kadyrkulov, spoke briefly during closing arguments, asking the court to consider that his son was “only an accomplice”.

No relatives or friends of the defendants attended the hearings, apart from their fathers and lawyers. By contrast, the court room was regularly filled with supporters of the victim’s family.

How the investigation turned around

For a long time, Galina could not openly talk about what was happening, as she had signed a non-disclosure agreement during the investigation. Her silence triggered rumors — including speculation that she had allegedly accepted money from the defendants’ families, which she could not publicly deny.

Photo from Galina Legkodimova’s Instagram account

Photo from Galina Legkodimova’s Instagram account

At the same time, she continued to appeal to state bodies. She met with representatives of the Presidential Administration, the Prosecutor General’s Office and the Interior Ministry. As a result, a senior investigator from Astana, 28-year-old Temirkhan Khazhmuratov, was sent to Atyrau.

He managed to recover deleted correspondence between Khairzhanov and Katimov, in which they discussed the plan to kill Yana. On 8 October 2025, the “Ne molchi” foundation published this correspondence, which had been read aloud in open court.

During the trial, the defendants’ fathers criticised both the foundation and Galina for publicising case materials. Activists replied that the hearings were open, and information read in court could be reported.

“Where does such cruelty come from?”

Psychologists and human rights defenders call the killing of Yana a textbook case of femicide — the gender-based killing of a woman.

Psychologist and gestalt therapist Shugyla Talgatkyzy notes that in the messages the men almost never called Yana by name, using nicknames or just “she” instead.

“This is a classic mechanism of dehumanisation. When a person is stripped of their individuality and reduced to an object, it becomes easier to justify aggression toward them,” she explained.

According to her, the tone of the correspondence — jokes, mockery and casual switching to everyday topics — indicates a lack of empathy and possible psychopathic tendencies.

Another key factor, she says, is an entrenched misogynistic attitude:

“The phrase ‘you didn’t lose a breadwinner’ clearly shows a view of women as secondary. If you are not a man, not a provider, your life is considered less valuable. In a society where harsh treatment of women is normalised, such crimes become possible.”

Judge Khamidullina voiced a similar concern in court: “Where does so much cruelty and bitterness come from?” she asked the defendants, stressing that they grew up in full families, had relatives and education.

Khairzhanov tried to explain his actions by saying he allegedly did not want his other girlfriend — whom he claimed he planned to marry — to find out about his relationship with Yana. In court, that second girlfriend stated he had never proposed to her.

Why this case is seen as a turning point

Lawyers and activists say this is the first time in Kazakhstan that a life sentence has been imposed in a case widely recognised as femicide. Previously, even for equally brutal murders of women, sentences typically ranged from 20 to 25 years in prison.

Experts believe this verdict could become a precedent and strengthen calls to introduce a separate article on gender-based violence and hate-motivated killings into Kazakhstan’s Criminal Code.

Meanwhile, according to UN Women, more than 140 women around the world are killed every day by intimate partners or family members.

For many in Kazakhstan, the Atyrau verdict is not just about one case. It has become a symbol of how society, institutions and the legal system respond — or fail to respond — to violence against women.

Galina Legkodimova during an interview after one of the court hearings, frame from video

Galina Legkodimova during an interview after one of the court hearings, frame from video

For Galina Legkodimova, however, the outcome has a different, very personal dimension.

“I didn’t have time to grieve,” she says. “I had to keep going, to the very end, for my daughter.”